Concerns about extremist exploitation of digital games and the radicalization of gamers have been increasing in recent years. Terrorist attacks with gamified elements, live-streamed on platforms like Twitch, and planned on game-adjacent platforms like Discord have in-part fueled these concerns. Members of the US congress have sent letters to game studios inquiring about their prevention efforts, and several companies have publicly increased such efforts to combat extremism on their games and platforms.

What is extremism and radicalization?

Extremism is the advocacy of extreme views, including the belief that an in-group’s success or survival can never be separated from the need for hostile action against an out group. Examples include misogyny, racism, and white nationalism.

Radicalization is the escalation over time of an in-groups [or individual’s] extremist orientation in the form of increasingly negative news about an out-group or the endorsement of increasingly hostile or violent actions against an out-group. Notably, there are several different definitions of radicalization, and many academics and government agencies acknowledge the distinct but at times overlapping versions of “cognitive radicalization,” focused on an individual’s internalization and support for violent extremist beliefs and “behavioral radicalization,” focused on an individual’s participation in violent actions.1

While the words extremism and radicalization are sometimes used interchangeably, the process of concern when it comes to games is the spread and normalization of extremist ideologies contributing to radicalization processes and potential mobilization to violent extremism within gaming spaces. This is the focus of this white paper.

What does extremism in games look like?

Extremist sentiment can be found everywhere, including our digital playgrounds. It is important to understand that this can take many forms.

It is important to note that many of the elements below are not inherently problematic. For example, the ability to create one’s own games, engagement in gaming communities, and utilizing games as pop culture all create wonderful opportunities for individuals to engage, create, and socialize. What is of note, however, is that these opportunities that can be utilized for positive outcomes can, and are, also being leveraged nefariously.

To learn about each of these topics, see the the full primer.

- Game content

- Propaganda

- Fundraising

- Normalization of rhetoric

Extremist ideology though voice or text chat is commonly reported in games. In a recent study of adult gamers, 20% of participants reported being exposed to white supremacist content, while 47% of women, 44% of African Americans, and 37% of LGBTQ+ players reported experiencing identity-based harassment.3

It is important to understand that this study is not saying that video games cause violence (which is a long-held belief that is not supported by research; see these resources for more) but rather games are spaces where extremist ideologies are commonly shared and can be normalized.

What does radicalization in games look like?

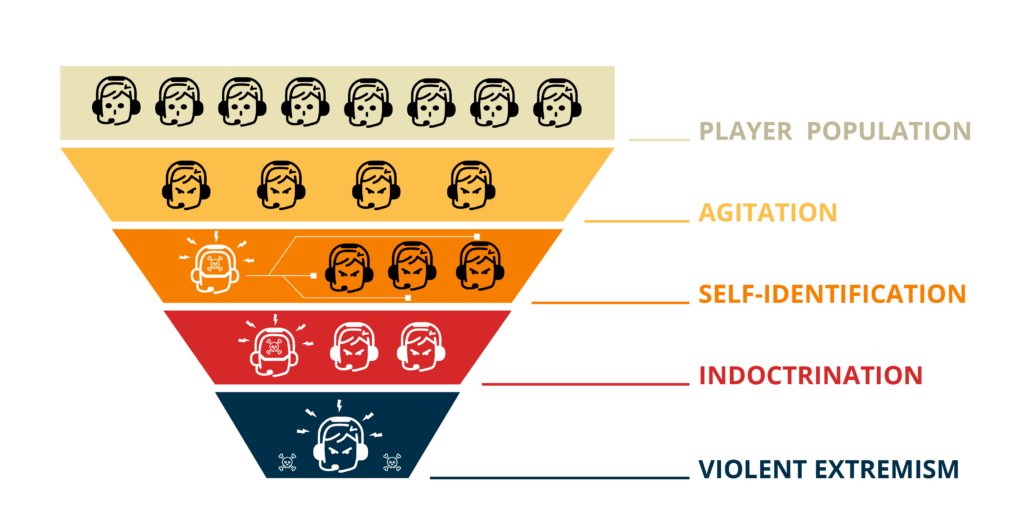

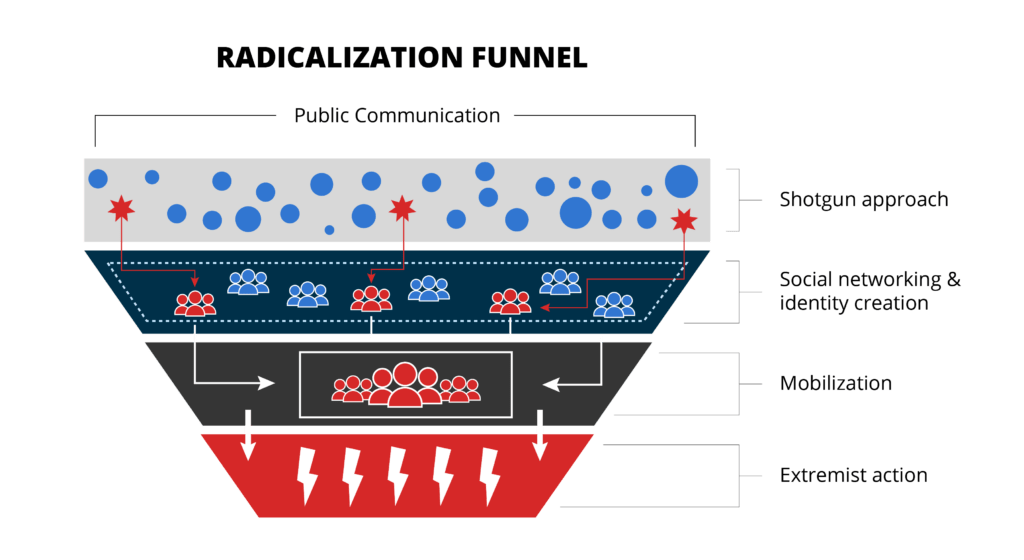

Extremist content is created and shared for the purpose of radicalization of individuals and society (i.e., normalizing extremist views, recruiting and mobilizing for violent extremism). What does the pathway of radicalization look like in games?

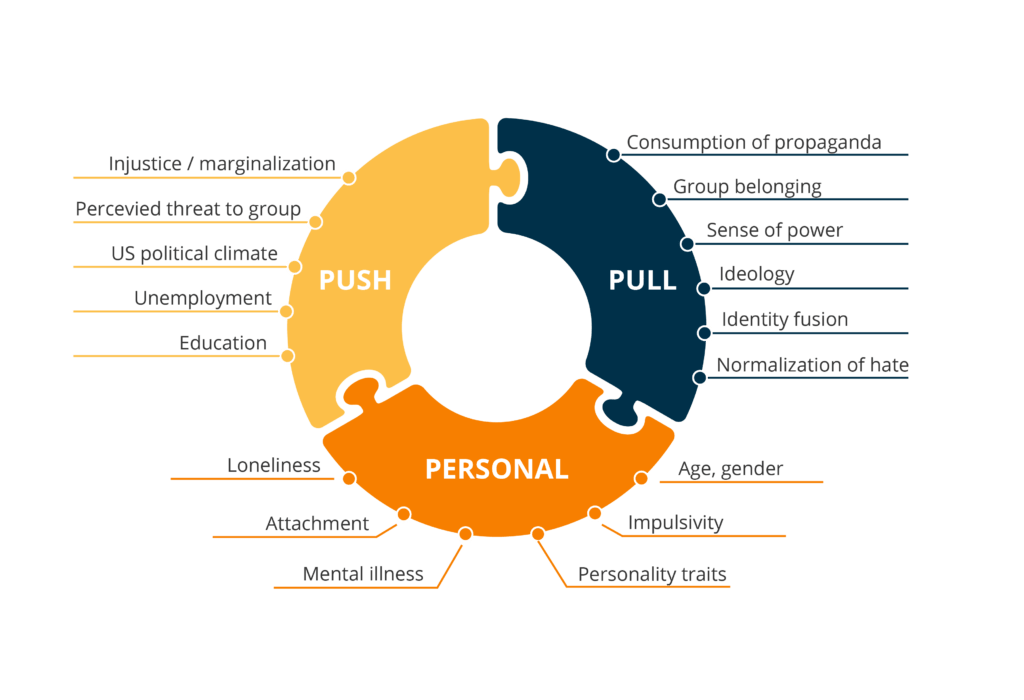

Regardless of the differences in definitions, experts generally agree that individuals don’t become radicalized overnight. Instead, there is a process that involves the combination of some underlying individual vulnerabilities or “personal factors,” as well as situations and events that “push” or “pull” an individual further down the pathway of radicalization.4 As individuals become increasingly radicalized, they may report increasingly radical beliefs and may be more likely to engage in hate and harassment-related behaviors in game and game-adjacent environments. It is at this point that other users, as well as trust and safety or community management staff become aware of the individual in this radicalization pipeline. It is unlikely the individual being radicalized will report they are being radicalized, as this process may be covert to the targeted user.

Because studio staff and other players may only see the consequences of the radicalization process (i.e. the hateful language used by the targeted user), there is often a conceptualization that the targeted user made an informed decision to start down a radicalization pathway. This serves to create a comfortable narrative about the targeted user’s use of hateful language, and simplifies the problem for the moderating body down to that of stopping that individual user from causing further harm in the community through muting or banning the user. While this may serve to stop the short-term harm from this individual user, it fails to address the source of the behavioral or cognitive escalation, and may unintentionally push the user further down the radicalization pathway by isolating them from the gaming community and reinforcing experiences of social rejection.

Where does radicalization in games happen?

Most in-game and gaming platform communication channels (such as team voice channels or private chats) are basic communication platforms, similar to a group text message chat or a phone call. Especially in the case of in-game text or voice chat, content is not saved in a way that can be referenced by the user in the future. Even text channels that save for the user to refer back to do not have features that allow for organization, such as those commonly available in more complex communication platforms such as Slack and Discord. As such, they are more suited for relationship building, propaganda dissemination, and early recruitment stages than they are for complex strategizing or planning. Though there is limited research into how extremists use voice and text chats in games, the research available supports these uses.5 Once extremists have connected with potential recruits, they may funnel them to game-adjacent platforms such as Discord, which allow for greater opportunities for coordination, as well as more convenient image sharing, organization of content, as well as voice and video chats.5

Individuals in the radicalization process can gain access to increasingly private spaces during the process of radicalization.6 Though terrorist actions may not be explicitly planned on gaming platforms, they are an important part of the radicalization process, and the more visible extremist content is on these platforms, the more such content may be normalized within the larger gaming community.

Are some players more vulnerable to radicalization?

Vulnerabilities to radicalization can be both personal and contextual, and are often split into the categories of “push,” “pull,” and “personal,” factors.4 Though these vulnerabilities may span across categories, these distinctions can be helpful for general understanding.

Any combination of these factors can make someone more vulnerable, however there are no specific constellations of factors that guarantee an individual will be radicalized.

What can make games more vulnerable to radicalization?

We know that radicalization can happen in many in-person and online spaces. However, many online games and gaming communities have several characteristics that make them particularly enticing to extremist actors and vulnerable to exploitation. Some of these factors, such as opportunities for community building, are the very things that give games some of their potential for great good. Several of these factors are discussed in more detail in the full report.

- Lack of effective moderation

- Community-building

- Gaming spaces with higher rates of toxicity

How do we move forward?

There are currently several efforts to better understand radicalization and extremism in game and game adjacent spaces, including efforts by game studios, several research organizations, nonprofits (such as the Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism , Extremism and Gaming Research Network, International Center for Counter-Terrorism, and ourselves at Take This) , and even national and international governing bodies (including the US Congress, Radicalization Awareness Network) Take This is currently developing resources like this paper, as well as delivering workshops and conducting research to understand how we can most effectively address these concerns and increase the safety of our online gaming spaces. Creating safe online gaming communities is a complex task, and involves the buy-in of all of us – below, we’ve outlined some of the recommended next steps for different stakeholders in our online communities.

Parents and Community Members

Many children and adolescents play online games, and this play can be an excellent way to build community and other skills. Parents and community members should be aware of the games their children play, and may benefit from playing or watching them play to understand more about the games and dynamics. Though parents won’t be able to monitor all the communication in online games (just as they won’t monitor all their communication at school or when their children are spending time in real life with friends), parents should have regular conversations about their experiences with online games and communities. More resources for parents and community members can be found here:

- PowerUpPact Gaming Resources

- Educational resources and chat support from NoFiltr

- Parent and caregiver guide (SPLC & PERIL)

- Educator supplement (SPLC & PERIL)

- Community guide (SPLC & PERIL)

- Online safety quiz and resources for Twitch

Game Industry and Lawmakers

See the full primer for recommendations.

This work is made possible by a grant from the Department of Homeland Security (DHS # EMW-2022-GR-00036).

References

- Neumann, P. R. (2013). The trouble with radicalization. International affairs, 89(4), 873-893. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.12049

- Lamphere-Englund, Galen, & Jessica White (2023). The online gaming ecosystem: Assessing socialisation, digital harms, and extremism mitigation efforts.” Global Network on Extremism and Technology (GNET). https://doi.org/10.18742/pub01-133.

- Anti-Defamation League (ADL). (2023). Hate is no game: Hate and Harassment in online games 2022. Retrieved form https://www.adl.org/resources/report/hate-no-game-hate-and-harassment-online-games-2022

- Vergani, M., Iqbal, M., Ilbahar, E., & Barton, G. (2020). The three Ps of radicalization: Push, pull and personal. A systematic scoping review of the scientific evidence about radicalization into violent extremism. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 43(10), 854-854.https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2018.1505686

- Lakhani, S. (2021). Video gaming and (violent) extremism: An exploration of the current landscape, trends, and threats. Radicalisation Awareness Network (Policy Support), European Commission, 2022-02.

- Ressa, Maria (2015). How to fight ISIS on social media. Rappler. Retrieved from https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/in-depth/86205-social-movements-fight-isis-social-media/

- Kowert, R., Martel, A., & Swann, W. B. (2022). Not just a game: Identity fusion and extremism in gaming cultures. Frontiers in Communication, 226. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2022.1007128